Genetic studies have traced modern, domestic cattle back 10,000 years ago to a single herd of wild oxen.

But while bovines may have changed in size and color—and adopted other variations based on breeding, evolution and external factors over the centuries—science suggests they haven’t changed all that much under the hood—anatomically speaking, that is.

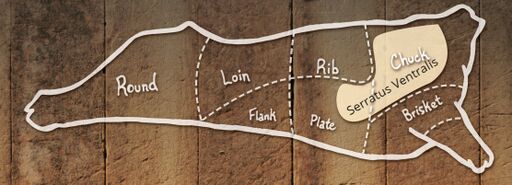

With the exception of the rare, genetic anomaly, cattle have always been made up of seven (or eight, if you’re old school) primals, 13 ribs and a musculature comprised of various, interwoven pieces we commonly refer to as beef cuts.

Most of the country’s population can rattle off at least a few of these typically found on their favorite steakhouse menus, but the reality is that there are a host of other cuts that allow for such immense versatility that they are almost unrecognizable from culture to culture.

Perhaps chief among these is the cut known in academia as the serratus ventralis—a well-marbled muscle that starts in the short plate and crosses eight rib bones before terminating in the chuck roll.

Most commonly, especially in America, this is known as the short rib.

What you’re reading is the first in a series dedicated solely to the short rib, from where it exists on a side of beef and how it is used around the globe to various, domestic preparation methods and alternative uses you may not have seen.

Anatomy of the Serratus Ventralis

Although it’s known for its robust marbling (remember, fat equals flavor) throughout, the serratus is also packed with a lot of collagen that breaks down best in a low and slow environment. This is classically achieved in a braise, under vacuum (sous vide) or smoker.

The end result produces a piece of meat that has incredible flavor—thanks to the marbling—while also being textually appealing to the human palate because the collagen has transformed into gelatin during the cooking process. Ever wonder why a short rib will sometimes jiggle like a plate of Jell-O? Here’s your answer.

Also, on the subject of anatomy, because the cut is so expansive, just cooking a so-called short rib isn’t necessarily a real indicator of what you’re working with.

Maybe you’re preparing a three-bone plate short rib. Maybe you’ve landed its four-bone compatriot, the chuck short rib. Maybe there’s no bone at all and you’re braising a Denver or an underblade.

Understand that this is the same cut that’s fabricated in such ways to produce everything from Jewish Flanken-style ribs, Korean galbi-style ribs, osso buco short ribs or even short rib tomahawks—not to mention good, old-fashioned, American barbecue ribs. In the chuck, you can make Denver steaks or, naturally, classic, boneless short ribs.

In short, although the same robust marbling and eating quality exists pretty much throughout, the region of the serratus ventralis that you’re working with is going to determine the dish that’s created.

So, let’s talk about those regions.

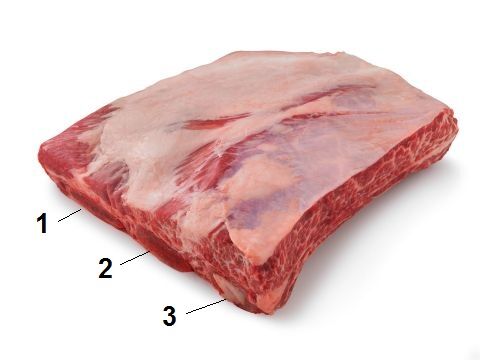

Short Plate

The plate short ribs that come out of the plate will be longer and contain three bone pieces (rib bones six, seven and eight, if you’re a meat science nerd), and are most often used for their impressiveness by barbecue aficionados everywhere in their smokers, like Kent and Barrett Black from Texas’ iconic Black’s BBQ.

Some chefs, like Simon Brown, use the length of the bone for plate presentation, peeling back the meat and tying it off before dropping it in a braise for a short rib tomahawk.

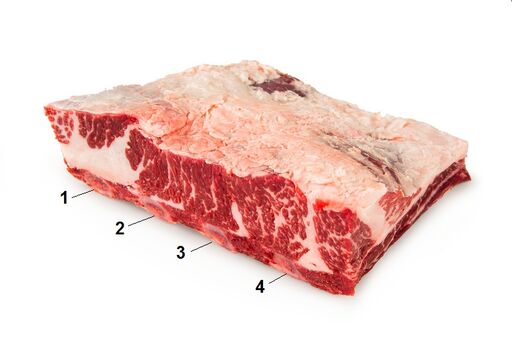

Chuck

One could write a book about the various cuts that can be pulled from the chuck.

Yet, for all the impressiveness of the short rib in the plate, the vast majority of the cut actually resides in the chuck.

This begins with four-bone chuck short ribs. Though generally shorter in length than their plate rivals, chuck short ribs actually contain more meat and are generally a tick cheaper.

These are an easy counterpoint to traditional pork ribs, or for diners who haven’t quite cross-trained enough to take down an entire plate short rib.

These may also be pulled off the bone to make boneless short ribs, but if that’s your end goal, consider using the next extensions of the serratus ventralis muscle: the chuck flap and the underblade.

The chuck flap and underblade are simply adjuncts of the same muscle, extending dorsally into the chuck or continuing toward the back. Just like their bone-in neighbors, they are at their very best in a low and slow cooking environment.

If aged appropriately (Meat Scientist Diana Clark recommends 28 days minimum), however, the chuck flap and underblade can be cut into steaks, which are growing in popularity under the name Denver steaks.

Travel Channel’s Andrew Zimmern even traveled to Ohio to experience a dry-aged Denver steak while filming an episode of “Bizarre Foods” in 2013.

It should be noted, however, Clark says, that while chuck flap is readily available, the underblade can only be procured by purchasing an entire chuck roll. This piece is typically found on a good, old-fashioned chuck roast your grandmother used to make, as well.

If you’d like to learn more about the science behind the short rib, take a moment and check out this video with renowned Meat Scientist Dr. Phil Bass, who is now a professor at the University of Idaho.

Be sure to come back to this space for part two of our series on the serratus ventralis, detailing the short rib in various cultures around the world.